Copyright © Frank O. Dodge. All rights reserved.

I missed World War One . . . it was over

four years before I was born . . . and I missed Desert Storm . . . I was

damn near seventy. But I participated in all the big stuff in

between.

Back in the late fifties I was ship's company on a transport that carried

troops and military dependents to and from the Brooklyn Army Terminal in

New York and Bremerhaven, West Germany. The two years I'd been making

this milk run had given me a fair whack at conversational German . . . enough,

at least, to get by in a bar-room.

The USS Kenneth Randolph was in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for repairs and, as

to be expected from a career sailor, I spent a good deal of my off-time evenings

in the slop chute . . . the Enlisted Men's Club . . . on base.

At that time the U.S. Government had given an old destroyer to the Bundesmarine

Deutschland . . . the West German Navy. She had pulled into the Brooklyn

Yard for some final refitting, and there were a lot of her crew beering-down

in the Club. When one of them found that I spoke a little German the

kids sort of gravitated to me. The fact that I was nearly forty and

they were mostly in their early twenties made no never-mind. Sailors

don't even think about things like that. You're all just guys in the

uniform. And sailors are all alike no matter what country's uniform

they wear.

We drank a lot of beer, and laughed a lot. I sang them the WWII songs

that I'd sung with my buddies and members of the British armed forces, and

they sang me the songs that had been popular with the Kreigsmarine and the

Wehrmacht. Pretty rousing stuff that called for a few more rounds.

![]()

That one evening I sat in a booth alone . . . my Kraut choir-members were

having to work late. I looked up as someone stopped by the table. It

was a German sailor, but one I hadn't met before. He was older than

the kids I'd been drinking with . . . about my own age. He pointed

to the pitcher of beer sitting in front of me and said, "I make a drink mit

you?"

I motioned for him to sit down. "Sure, Mac." I poured him a glass.

"Ich spreche ein wenig Deutsch. Was gibt?"

He grinned and replied in German, "You speak German. That's good, my

English is pretty bad."

I laughed. "I said I speak a little German, and it's pretty

bad, too. No problem. We'll make out."

I emptied the pitcher and stood up. The man looked at me. "I'd

buy this round, but I doubt they take Reichmarks here."

"Forget it."

I was half way to the bar before the discrepancy hit me. He'd said

'Reichmarks'. The Reichmark had gone out with Hitler. The present

German currency was the Deutschmark. I shrugged. A Freudian slip.

After all, the guy was my age and probably fought for Hitler. No

big deal. That war had been over for fourteen years. No hard

feelings.

When I got back to the booth it seemed to me that there was something strange

about my new friend. I couldn't get a bearing on it. I put it

down to the lighting, but for a moment it had almost looked like he . . .

flickered . . . .

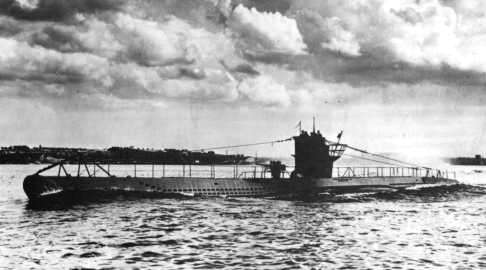

It was inevitable, of course, that the war came up. "I sailed the North

Atlantic back in '42 and '43," I mentioned. "I was in what we called

the Armed Guard . . . Navy gunners aboard merchant ships."

The sailor took a swallow of his beer. " I was in the North Atlantic,

also, in '42 . . . Unterseeboot." There was a tinge of sadness in his

voice.

I grinned. "You U-Boat guys sure had the hell scared out of me!"

He grinned back and said something that had never before crossed my mind.

He said, "Well, I was scared, too."

"No kidding?"

"No kidding."

"You guys practically crawled out of the water knocking off our shipping

up and down the Atlantic Coast, let me tell you. There were rumors

that you guys would even anchor off Long Island and come ashore on

liberty."

My friend's grin broadened. He downed his beer, and I poured. "We

did. There were so many foreign uniforms on Broadway nobody looked

at us twice. American girls are very friendly. They thought we

were Hollanders."

Again I put it down to the lighting, but for an instant I had the eerie

impression that the seat opposite me was empty. Maybe I'd had more

beer than I thought. I shook my head. He looked solid enough.

"That doesn't surprise me." I laughed. "Hell, you people treated

our coastline like it was your own! In late '42 I was coming back from

North Africa on a Liberty ship. The convoy was lined up to enter New

York harbor . . . almost half of them had already made the turn . . . and

all of a sudden one of our escort vessels came hootin' and hollerin' up our

port side. About two ships ahead of us he started flinging ash-cans

all over the place, and when we passed the spot there was a big oil slick

. . . ."

I stopped. "Sorry, Mac. Maybe you knew some of the guys on that

sub."

Once again that sad expression flicked over his face. "I did . . .

." He leaned forward and rested his forearms on the table.

"American, we fought, you and I, you for your side, I for mine. It

was never anything personal. Some of us died and some of us lived.

Der Krieg, nicht wahr? Some died and some lived . . . ."

He drew in a deep breath. "Some died . . . . American, some of us who

once fought your country now owe your country a great debt of gratitude for

something that it has just done for us. I just came ashore to tell

someone that . . . ."

He finished his beer and stood up. "In my Navy every lower rating salutes

a higher one. I see from your stripes that you are Bootsmann. I

only Matrose . . . seaman." He saluted. "Thank you, American, for your

country's compassion."

I returned the salute, wondering what the hell he was talking about. He

turned and walked away into the crowd, leaving me puzzled.

The only thing that I could think of that the U. S. had recently done for

Germany was to give them a worn-out old destroyer. Why had he come

ashore just to thank someone for

that?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

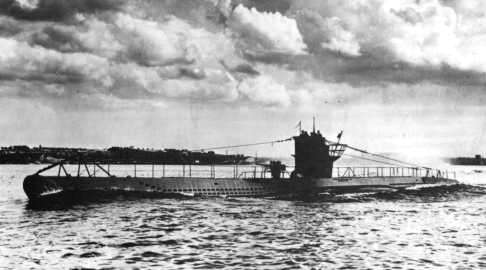

No one can ever know the icy feeling that ran

up my spine at noon the next day. I was watching the midday news in

the First Class Petty Officers' Mess aboard ship when the anchorman said,

". . . Earlier today Captain McClowsky, a spokesman for the Navy, told reporters

that the Navy had raised a World War Two German submarine that had been sunk

in November of nineteen forty-two less than a mile outside New York harbor.

Navy divers attached and inflated floats to the sunken U-Boat and towed

it to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The vessel will be pumped out and the men of her crew will be returned to

Germany for proper burial. Captain McClowsky stated, "These men have

been away from home for a long time. Every sailor deserves to return

to his home port when the voyage is over."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()